Balancing Act: The Debate Over International Student Numbers in Australia

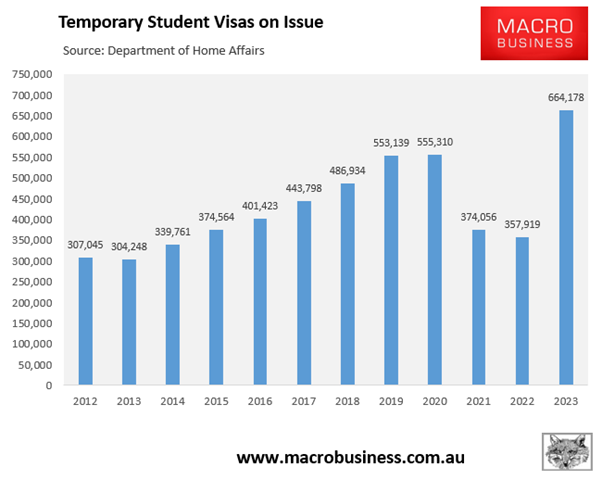

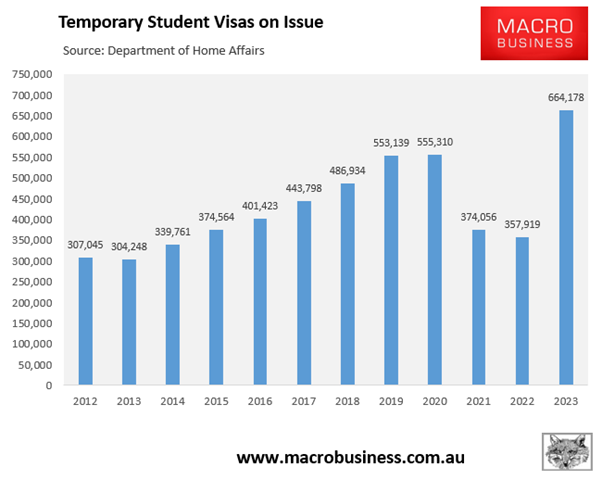

The most recent data on temporary visas provided by the Department of Home Affairs revealed that a record 664,200 student visas were on issue in September, representing an annual growth of 306,300:

The surge in international students flocking to Australia has undoubtedly redefined the landscape of higher education in the country. With a record-breaking influx of student and graduate visas, the impact has reverberated not only within educational institutions but also in the wider Australian society, significantly impacting the housing market.

Recent data from the Department of Home Affairs has spotlighted a staggering increase in student visa numbers, reaching unprecedented levels in September. The sheer magnitude of this surge, which surpassed the 2019 peak by around 110,000 visas, showcases the immense attraction Australia holds for international students seeking education and opportunities.

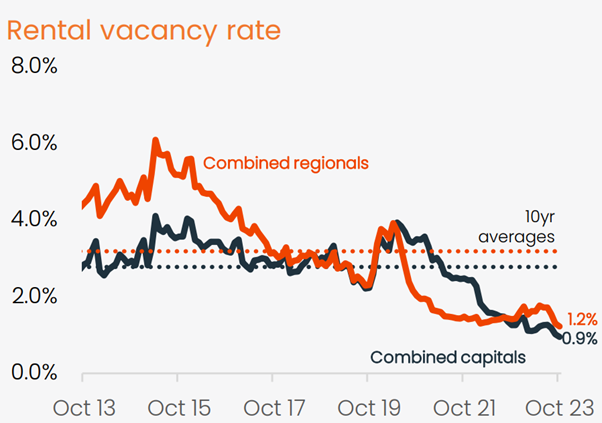

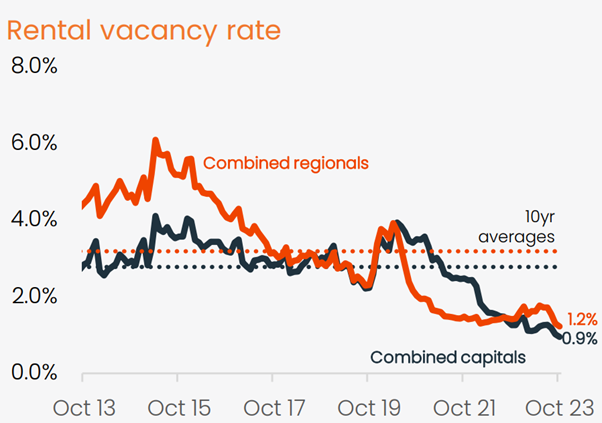

However, as the influx continues, it has played a pivotal role in Australia’s rental crisis, triggering a steep decline in rental vacancy rates and surging rental prices across the combined capital cities. This surge has contributed to housing market pressures, escalating inflation, and interest rates.

In response to these mounting challenges, there have been fervent calls to cap international student numbers. Proponents of this stance highlight the strains on the housing market and the consequential impact on inflation and interest rates. However, these calls have met resistance from lobbyists within the higher education sector, warning about the potential revenue losses the sector might face if such caps were imposed.

Jake Foster, chief commercial officer with student recruitment firm AECC, argues against capping student numbers, citing a modest increase in international student figures and the prevalence of purpose-built student accommodations. Nonetheless, the contrasting data reveals a more substantial increase in student visas and challenges the perception of where international students reside.

The discourse surrounding capping student numbers has sparked a debate, with economist Rohan Pitchford from the Australian National University dismissing the idea as “nonsensical.” Pitchford emphasizes the positive impact of international students on labor supply and its anti-inflationary role, contrary to the mounting pressures on the rental market.

Amidst this debate, the narrative questions the stance of Australian universities, portraying them as not-for-profit entities benefitting significantly from student fees without contributing taxes. This viewpoint contrasts the corporatized approach of universities, aligning with profit-driven corporations, yet exempt from tax liabilities.

Advocates for capping international student numbers propose several strategies to achieve a balanced equation, ranging from limiting enrollments within courses and institutions to imposing requirements for on-campus accommodations proportionate to enrolments. These measures aim to alleviate pressure on the rental market while aligning the costs and benefits for both universities and Australians.

Suggestions extend to tightening entry requirements, penalizing poorly performing institutions, reducing work rights for international students, and implementing financial levies on institutions per enrolled international student. The overarching goal is to strive for a smaller cohort of higher-quality students, thereby optimizing the benefits for both the education sector and the broader Australian community.

The discourse culminates in a reflection on the implications of recent migration pacts with India signed earlier in the year, potentially complicating efforts to curb international student numbers and impacting educational quality.

As Australia navigates the complexities of this unprecedented surge in international students, the conversation continues to evolve, weighing the interests of the education sector against the broader socio-economic impacts on the nation. The path forward demands a delicate balance between attracting global talent and ensuring sustainable growth, underscoring the need for nuanced policies that cater to the interests of both students and the Australian populace.

As you can see above, student visa numbers in September were around 110,000 higher than the September 2019 peak.

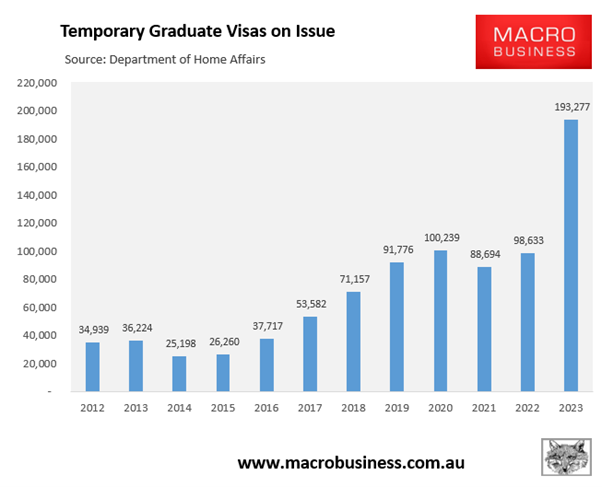

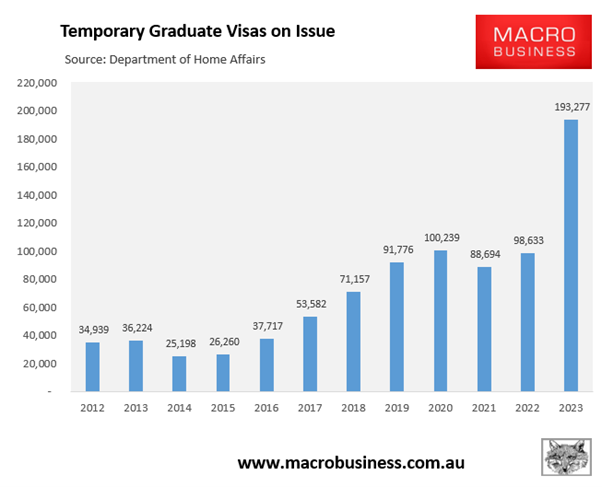

Graduate visas are also at an all-time high, with 193,300 on issue in September, up by around 95,000 over the year:

This means that in September, approximately one in every 30 people in Australia held a student or graduate visa—a truly astounding number.

The record surge in international students has played a major role in Australia’s rental crisis, with rental vacancy rates across the combined capital cities having plummeted to a record low 0.9%, along with rampant rental price inflation.

Source: CoreLogic

Given the unprecedented pressures on the nation’s housing market, which is also helping to drive-up inflation and interest rates, there are now calls to cap international student numbers.

As usual, these calls have been met with opposition from lobbyists in the higher education space who warn that capping student numbers would reduce revenues earned by the sector:

“There are only 3% to 4% more international students studying in Australia in 2023 than there were in 2019, many of whom live in purpose-built student accommodation”, said Jake Foster, chief commercial officer with student recruitment firm AECC.

“It took the Australian international education sector years to recover from COVID border closures; we need to be very careful of the messages we send to prospective international students considering Australia”, he said.

Actually Jake, total student visas on issue in September 2023 were 20% above September 2019. And the overwhelming majority of international students do not live in “purpose-built student accommodation”. nice try though.

Rohan Pitchford, an economist with Australian National University, also claimed capping student numbers was “nonsensical”.

“It also ignores the positive impact such students have in supply of labour to employers who are struggling to find workers at the minimum wage. This aspect is anti-inflationary”, he wrote on Twitter (X).

Righto Rohan, so we should ignore the immense pressure on the rental market, which is driving Australians into poverty and homelessness?

Let’s be real here. Australian universities are not-for-profit organisations that currently do not pay tax (unlike other ‘export’ industries). This is despite universities acting like corporatised, profit-maximising corporations with senior leadership groups that get paid exorbitant salaries.

The universities, rather than taxpayers, are therefore ‘clipping the ticket’ and collecting the economic rents from Australia’s immigration system via student fees. They are privatising the gains from record immigration while the external costs are being pushed onto Australians at large, most notably renters. Everybody who is not a vested interest can recognise that the federal government should actively lower international student numbers from their current unsustainable levels.

This could be achieved by limiting international students to a maximum percentage of enrolments within both courses and institutions. Numbers could also be capped by requiring universities to provide on-campus accommodation to international students in proportion to their enrolments.

This policy would relieve pressure on Australia’s private rental market while also ensuring that the costs and benefits to universities and Australians from the international student trade are better aligned.

Other ways to reduce international student numbers could involve:

•Tightening entry requirements, including English-language proficiency and proof of finances.

•Tightening licensing and performance standards for private colleges.

•Penalising poorly performing institutions and closing down ‘ghost colleges’.

•Capping the amount of finder fees and kickbacks that can be paid by institutions to education and migration agents.

•Reducing the generosity of work rights for international students and graduates.

•Charging institutions, a levy per international student enrolled to ensure that Australians receive a financial return from the trade, similar to how a sovereign wealth fund collects revenue from mineral exports.

In summary, Australia should aim for a smaller number of higher-quality students.

Unfortunately, the Albanese government took a giant step backwards when it signed two migration pacts with India earlier this year with the explicit aim of boosting the number of Indians studying, living and working in Australia.

These migration pacts will make it more difficult to lower international student numbers to sustainable levels, while also degrading quality.